How to Easily Remove Packages Installed From Source in Linux

In one of our previous articles, we’d shown you how to install and uninstall software in Linux outside the regular package managers. In that, we also saw that well-constructed software comes with built-in uninstallers. This way, you can remove the packages as easily as you install them.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. There are plenty of packages out in the wild which don’t allow for clean removal. Sometimes you have no choice but to use a package like this because you need the functionality. However, there is a solution to the problem. In this article, we’ll show you how to use the software called “stow” to easily remove packages installed from in Linux.

Step 1: Install Stow

The “stow” package should be available in your regular package repositories. In this example, we are using CentOS so we need the extended EPEL libraries. You can install them using the command:

yum install epel-release

And after that, install stow like this:

yum install stow

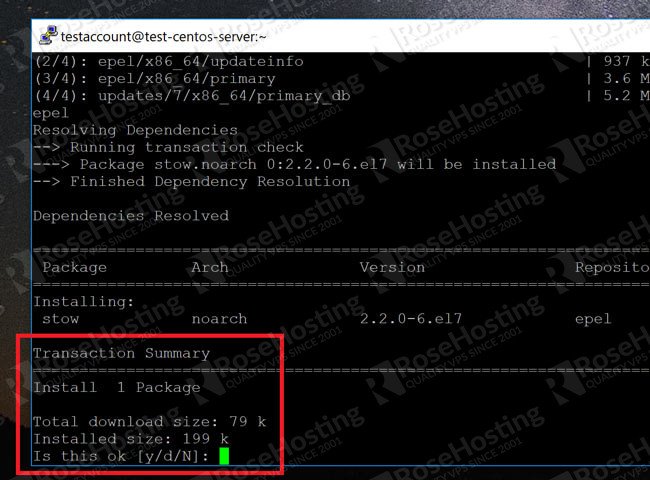

Press yes to confirm the installation:

Now that stow is installed, we have to choose where to store our package files.

Step 2: Choose Where to Store Package Files

The normal “make install” command copies the package files into a variety of places. Stow works by keeping them all in one place in a single directory, and then creating symlinks to where they should have gone originally.

So we need to choose a directory for where stow keeps all the package files. By convention, this is usually:

/usr/local/stow/

And in this location, we have one single directory for each package. So if we want to install the “hello” program that we used as an example in the previous article, the files will be stored in:

/usr/local/stow/hello

But this location can be anything. Just to show, we’ll be storing the files in the following location:

/home/bhagwad/stow/

Step 3: Using “make install” with the “prefix” Option

We saw in the previous article that installing from source requires these commands:

./configure

make

make install

To install with stow, we just change the last step to:

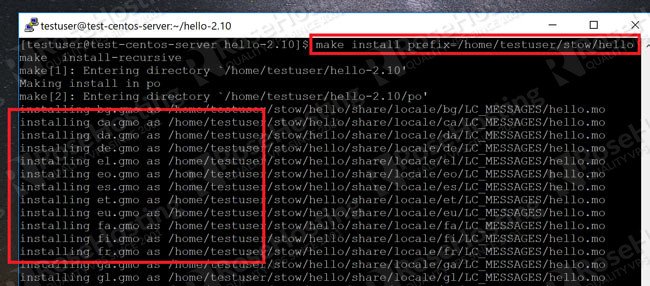

make install prefix=/home/testuser/stow/hello

The “prefix” option tells us to place the packages in the given location. This location is nothing but the selected directory in Step 2 with the package name added on as a separate folder. This causes the files to be installed into the given location as shown here:

Now we have all the files required for the package in a folder in the stow directory. Time for the magic to happen!

Step 4: Completing the Installation with stow

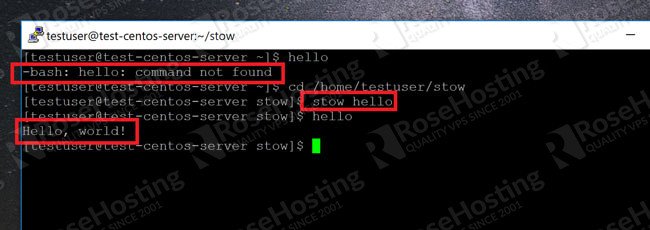

To install the package, first “cd” into the stow directory like this:

cd /home/testuser/stow

Ensure that the folder with the files is just one directory below your current location. Now type:

stow hello

That’s it! The package is now installed on your system. Here’s a screenshot of the “hello” command working as intended:

But wait. The real benefit is yet to come. Uninstallation.

Step 5: Removing Packages

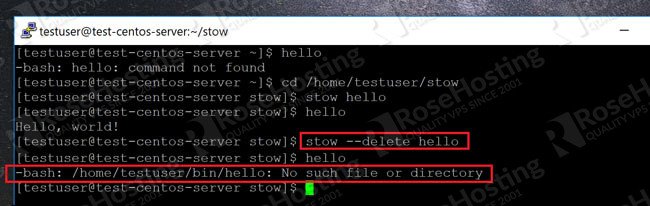

The coolest part about stow is how easy it is to remove packages from the system. No need to keep the source packages or anything. Just navigate to the stow directory as in Step 4 and type:

stow –delete hello

And it’s done! You can see below that the command no longer works after this step:

As far as the system is concerned, the package has been completely removed! It’s good to remember that the files haven’t actually vanished. They’re still in the “hello” directory. You could just as easily install the package again with the stow command. If you don’t require the files anymore, just delete the “hello” folder and your system is clean!

We recommend using stow every single time you install a package from source. It’s not worth the risk to have a badly written package spray your system with files everywhere, and which are a nuisance to remove afterward. Stow ensures that they’re all neatly contained in one location, then keeps track of the symlinks and deletes them afterward. It’s a fantastic solution!

Of course, if you are one of our Managed VPS hosting customers, you don’t have to remove packages installed from source, simply ask our admins, sit back and relax. Our admins will do this for you immediately.

PS. If you liked this post about how to easily remove packages installed from source in Linux, please share it with your friends on the social networks using the buttons below or simply leave a comment in the comments section. Thanks.

Go to Settings

Go to Settings

Use Windows + Space to change keyboard in use

Use Windows + Space to change keyboard in use Move the keyboard up the order

Move the keyboard up the order