For as long as GNU/Linux systems have existed, system administrators have needed to recover from root filesystem corruption, accidental configuration changes, or other situations that kept the system from booting into a “normal” state.

Linux distributions typically offer one or more menu options at boot time (for example, in the GRUB menu) that can be used for rescuing a broken system; typically they boot the system into a single-user mode with most system services disabled. In the worst case, the user could modify the kernel command line in the bootloader to use the standard shell as the init (PID 1) process. This method is the most complex and fraught with complications, which can lead to frustration and lost time when a system needs rescuing.

Most importantly, these methods all assume that the damaged system has a physical console of some sort, but this is no longer a given in the age of cloud computing. Without a physical console, there are few (if any) options to influence the boot process this way. Even physical machines may be small, embedded devices that don’t offer an easy-to-use console, and finding the proper serial port cables and adapters and setting up a serial terminal emulator, all to use a serial console port while dealing with an emergency, is often complicated.

When another system (of the same architecture and generally similar configuration) is available, a common technique to simplify the repair process is to extract the storage device(s) from the damaged system and connect them to the working system as secondary devices. With physical systems, this is usually straightforward, but most cloud computing platforms can also support this since they allow the root storage volume of the damaged instance to be mounted on another instance.

Once the root filesystem is attached to another system, addressing filesystem corruption is straightforward using fsck and other tools. Addressing configuration mistakes, broken packages, or other issues can be more complex since they require mounting the filesystem and locating and changing the correct configuration files or databases.

Using systemd

Before systemd, editing configuration files with a text editor was a practical way to correct a configuration. Locating the necessary files and understanding their contents may be a separate challenge, which is beyond the scope of this article.

When the GNU/Linux system uses systemd though, many configuration changes are best made using the tools it provides—enabling and disabling services, for example, requires the creation or removal of symbolic links in various locations. The systemctl tool is used to make these changes, but using it requires a systemd instance to be running and listening (on D-Bus) for requests. When the root filesystem is mounted as an additional filesystem on another machine, the running systemd instance can’t be used to make these changes.

Manually launching the target system’s systemd is not practical either, since it is designed to be the PID 1 process on a system and manage all other processes, which would conflict with the already-running instance on the system used for the repairs.

Thankfully, systemd has the ability to launch containers, fully encapsulated GNU/Linux systems with their own PID 1 and environment that utilize various namespace features offered by the Linux kernel. Unlike tools like Docker and Rocket, systemd doen’t require a container image to launch a container; it can launch one rooted at any point in the existing filesystem. This is done using the systemd-nspawn tool, which will create the necessary system namespaces and launch the initial process in the container, then provide a console in the container. In contrast to chroot, which only changes the apparent root of the filesystem, this type of container will have a separate filesystem namespace, suitable filesystems mounted on /dev, /run, and /proc, and a separate process namespace and IPC namespaces. Consult the systemd-nspawn man page to learn more about its capabilities.

An example to show how it works

In this example, the storage device containing the damaged system’s root filesystem has been attached to a running system, where it appears as /dev/vdc. The device name will vary based on the number of existing storage devices, the type of device, and the method used to connect it to the system. The root filesystem could use the entire storage device or be in a partition within the device; since the most common (simple) configuration places the root filesystem in the device’s first partition, this example will use /dev/vdc1. Make sure to replace the device name in the commands below with your system’s correct device name.

The damaged root filesystem may also be more complex than a single filesystem on a device; it may be a volume in an LVM volume set or on a set of devices combined into a software RAID device. In these cases, the necessary steps to compose and activate the logical device holding the filesystem must be performed before it will be available for mounting. Again, those steps are beyond the scope of this article.

Prerequisites

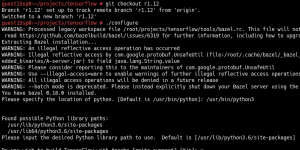

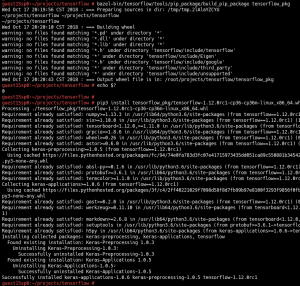

First, ensure the systemd-nspawn tool is installed—most GNU/Linux distributions don’t install it by default. It’s provided by the systemd-container package on most distributions, so use your distribution’s package manager to install that package. The instructions in this example were tested using Debian 9 but should work similarly on any modern GNU/Linux distribution.

Using the commands below will almost certainly require root permissions, so you’ll either need to log in as root, use sudo to obtain a shell with root permissions, or prefix each of the commands with sudo.

Verify and mount the fileystem

First, use fsck to verify the target filesystem’s structures and content:

$ fsck /dev/vdc1

If it finds any problems with the filesystem, answer the questions appropriately to correct them. If the filesystem is sufficiently damaged, it may not be repairable, in which case you’ll have to find other ways to extract its contents.

Now, create a temporary directory and mount the target filesystem onto that directory:

$ mkdir /tmp/target-rescue

$ mount /dev/vdc1 /tmp/target-rescue

With the filesystem mounted, launch a container with that filesystem as its root filesystem:

$ systemd-nspawn –directory /tmp/target-rescue –boot — –unit rescue.target

The command-line arguments for launching the container are:

- –directory /tmp/target-rescue provides the path of the container’s root filesystem.

- –boot searches for a suitable init program in the container’s root filesystem and launches it, passing parameters from the command line to it. In this example, the target system also uses systemd as its PID 1 process, so the remaining parameters are intended for it. If the target system you are repairing uses any other tool as its PID 1 process, you’ll need to adjust the parameters accordingly.

- — separates parameters for systemd-nspawn from those intended for the container’s PID 1 process.

- –unit rescue.target tells systemd in the container the name of the target it should try to reach during the boot process. In order to simplify the rescue operations in the target system, boot it into “rescue” mode rather than into its normal multi-user mode.

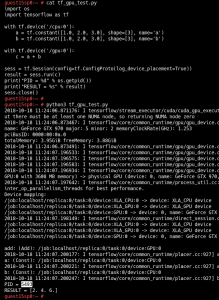

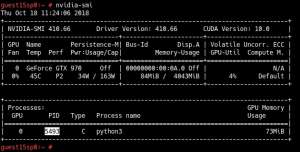

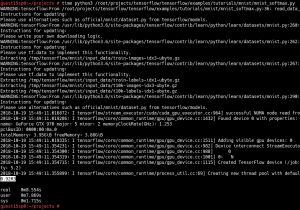

If all goes well, you should see output that looks similar to this:

Spawning container target-rescue on /tmp/target-rescue.

Press ^] three times within 1s to kill container.

systemd 232 running in system mode. (+PAM +AUDIT +SELINUX +IMA +APPARMOR +SMACK +SYSVINIT +UTMP +LIBCRYPTSETUP +GCRYPT +GNUTLS +ACL +XZ +LZ4 +SECCOMP +BLKID +ELFUTILS +KMOD +IDN)

Detected virtualization systemd-nspawn.

Detected architecture arm.

Welcome to Debian GNU/Linux 9 (Stretch)!

Set hostname to <test>.

Failed to install release agent, ignoring: No such file or directory

[ OK ] Reached target Swap.

[ OK ] Listening on Journal Socket (/dev/log).

[ OK ] Started Dispatch Password Requests to Console Directory Watch.

[ OK ] Reached target Encrypted Volumes.

[ OK ] Created slice System Slice.

Mounting POSIX Message Queue File System…

[ OK ] Listening on Journal Socket.

Starting Set the console keyboard layout…

Starting Restore / save the current clock…

Starting Journal Service…

Starting Remount Root and Kernel File Systems…

[ OK ] Mounted POSIX Message Queue File System.

[ OK ] Started Journal Service.

[ OK ] Started Remount Root and Kernel File Systems.

Starting Flush Journal to Persistent Storage…

[ OK ] Started Restore / save the current clock.

[ OK ] Started Flush Journal to Persistent Storage.

[ OK ] Started Set the console keyboard layout.

[ OK ] Reached target Local File Systems (Pre).

[ OK ] Reached target Local File Systems.

Starting Create Volatile Files and Directories…

[ OK ] Started Create Volatile Files and Directories.

[ OK ] Reached target System Time Synchronized.

Starting Update UTMP about System Boot/Shutdown…

[ OK ] Started Update UTMP about System Boot/Shutdown.

[ OK ] Reached target System Initialization.

[ OK ] Started Rescue Shell.

[ OK ] Reached target Rescue Mode.

Starting Update UTMP about System Runlevel Changes…

[ OK ] Started Update UTMP about System Runlevel Changes.

You are in rescue mode. After logging in, type “journalctl -xb” to view

system logs, “systemctl reboot” to reboot, “systemctl default” or ^D to

boot into default mode.

Give root password for maintenance

(or press Control-D to continue):

In this output, you can see systemd launching as the init process in the container and detecting that it is being run inside a container so it can adjust its behavior appropriately. Various unit files are started to bring the container to a usable state, then the target system’s root password is requested. You can enter the root password here if you want a shell prompt with root permissions, or you can press Ctrl+D to allow the startup process to continue, which will display a normal console login prompt.

When you have completed the necessary changes to the target system, press Ctrl+] three times in rapid succession; this will terminate the container and return you to your original shell. From there, you can clean up by unmounting the target system’s filesystem and removing the temporary directory:

$ umount /tmp/target-rescue

$ rmdir /tmp/target-rescue

That’s it! You can now remove the target system’s storage device(s) and return them to the target system.

The idea to use systemd-nspawn this way, especially the –boot parameter, came from a question posted on StackExchange. Thanks to Shibumi and kirbyfan64sos for providing useful answers to this question!

Source

Intrinsyc’s compact “Open-Q 605” SBC for computer vision and edge AI applications runs Android 8.1 and Qualcomm’s Vision Intelligence Platform on Qualcomm’s IoT-focused, octa-core QCS605.

Intrinsyc’s compact “Open-Q 605” SBC for computer vision and edge AI applications runs Android 8.1 and Qualcomm’s Vision Intelligence Platform on Qualcomm’s IoT-focused, octa-core QCS605.