If you, like me, like to own your own data, chances are you also like to purchase movies and TV shows on Blu-Ray or DVD discs. And you may also like to make ISOs of the videos to keep exact digital copies, as I do.

For a little while, it might be manageable to have a bunch of files stored in some sort of directory structure. However, as your collection grows, you may want features like resuming from a specific spot; keeping track of where you left off watching a video (i.e., its watched status); storing episode or movie summaries and movie trailers; buying media in multiple languages; or just having a sane way to play all those ISOs you ripped. This is where Kodi comes in.

What is Kodi?

Modern Kodi is the successor to Xbox Media Player, which was discontinued way back in 2003. In June 2004, Xbox Media Center (XBMC) was born. For over three years, XBMC remained on the Xbox. Then in 2007, work began in earnest to port the media player over to Linux.

Aside from some uninteresting technical history, things remained fairly stable, and XBMC grew in prominence. By 2014, XBMC had a thriving community, and its core functionality grew to include playing games, streaming content from the web, and connecting to mobile devices. This, combined with legal issues involving Xbox in the name, lead the team behind XBMC to rename it Kodi. Kodi is now branded as an “entertainment hub that brings all your digital media together into a beautiful and user-friendly package.”

Today, Kodi has an extensible interface that has allowed the open source community to build new functionality using plugins. Note that, as with all open source software, Kodi’s developers are not responsible for the ecosystem’s plugins.

How do I start?

For Ubuntu-based distributions, Kodi is just a few short commands away:

sudo apt install software-properties-common

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:team-xbmc/ppa

sudo apt update

sudo apt install kodi

In Arch Linux, you can install the latest version from the community repo:

sudo pacman -S kodi

Packages were maintained for Fedora 26 by RPM Fusion (referenced in the Kodi documentation). I tried it on Fedora 29, and it was quite unstable. I’m sure that this will improve over time, but my experience is that Fedora 29 is not the ideal platform for Kodi.

OK, it’s installed… now what?

Before we proceed, note that I am making two assumptions about your media content:

- You have your own local, legally attained content.

- You have already transferred this content from your DVDs, Blu-Rays, or another digital distribution source to your local directory or network.

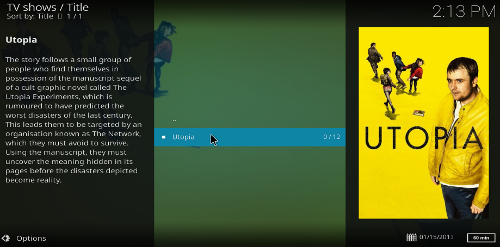

Kodi uses a scraping service to pull down TV and movie metadata. For Kodi to match things appropriately, I recommend adopting a directory and file-naming structure similar to this:

Utopia

├── Utopia.S01.dvd_rip.x264

│ ├── Utopia.S01E01.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

│ ├── Utopia.S01E02.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

│ ├── Utopia.S01E03.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

│ ├── Utopia.S01E04.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

│ ├── Utopia.S01E05.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

│ ├── Utopia.S01E06.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

└── Utopia.S02.dvd_rip.x264

├── Utopia.S02E01.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

├── Utopia.S02E02.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

├── Utopia.S02E03.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

├── Utopia.S02E04.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

├── Utopia.S02E05.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

└── Utopia.S02E06.dvd_rip.x264.mkv

I put the source (my DVD) and the codec (x264) in the title, but these are optional. For a TV series, you can include the episode title in the filename if you like. The important part is SxxExx, which stands for Season and Episode. This is how Kodi (and by extension the scrapers) can identify your media.

Assuming you have organized your media like this, let’s do some basic Kodi configuration.

Add video sources

Adding video sources is a simple, six-step process:

- Enter the files section

- Select Files

- Click Add source

- Browse to your source

- Define the video content type

- Refresh the metadata

If you’re impatient, feel free to navigate these steps on your own. But if you want details, keep reading.

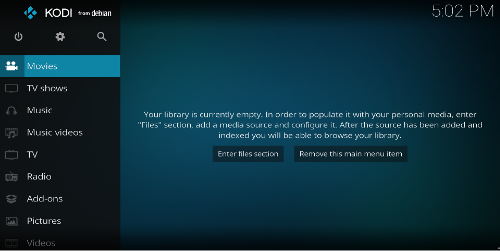

When you first launch Kodi, you’ll see the home screen below. Click Enter files section. It doesn’t matter whether you do this under Movies (as shown here) or TV shows.

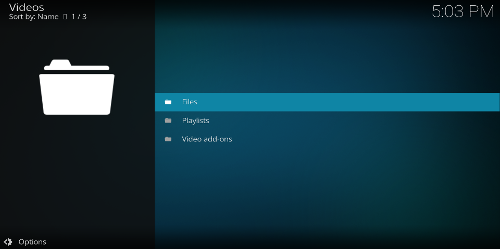

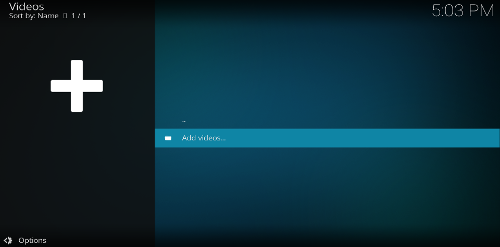

Next, select the Videos folder, click Files, and choose Add videos.

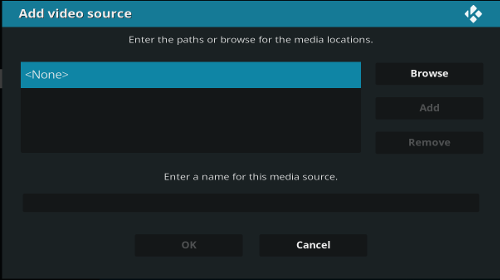

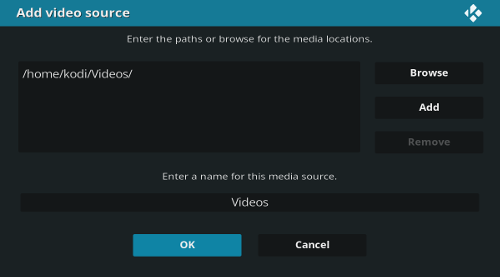

Either click on None and start typing the path to your files or click Browse and use the file navigation.

As you can see in this screenshot, I added my local Videos directory. You can set some default options through Browse, such as specifying your home folder and any drives you have mounted—maybe on a network file system (NFS), universal plug and play (UPnP) device, Windows Network (SMB/CIFS), or zeroconf. I won’t cover most of these, as they are outside the scope of this article, but we will use NFS later for one of Kodi’s advanced features.

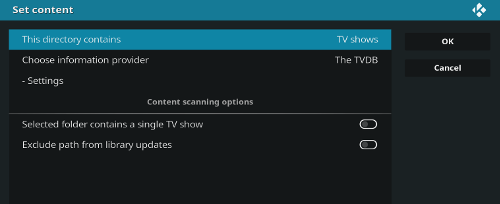

After you select your path and click OK, identify the type of content you’re working with.

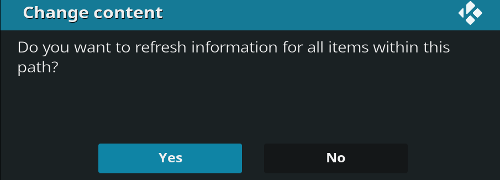

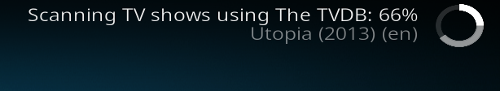

Next, Kodi prompts you to refresh the metadata for the content in the selected directory. This is how Kodi knows what videos you have and their synopsis, cast information, thumbnails, fan art, etc. Select Yes, and you can watch the video-scanning progress in the top right-hand corner.

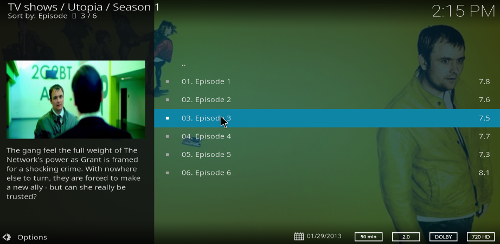

When the scan completes, you’ll see lots of useful information, such as video overviews and season and episode descriptions for TV shows.

You can use the same process for other types of content, such as music or music videos.

Increase functionality with add-ons

One of the most interesting things about open source projects is that the community often extends them well beyond their initial scope. Kodi has a very robust add-on infrastructure. Most of them are produced by Kodi fans who want to extend its default functionality, and sometimes companies (such as the Plexcontent streaming service) release official plugins. Be very careful about adding plugins from untrusted sources. Just because you find an add-on on the internet does not mean it is safe!

Be warned: Add-ons are not supported by Kodi’s core team!

Having said that, there are many useful add-ons that are worth your consideration. In my house, we use Kodi for local playback and Plex when we want to access our content outside the house—with one exception. One of our rooms has a poor WiFi signal. I rip my Blu-Rays to very large MKV files (usually 20–40GB each), and the WiFi (and therefore Kodi) can’t handle the files without stuttering. Although you can (and we have) dug into some of the advanced buffering options, even those tweaks have proved insufficient with very large files. Since we already have a Plex server that can transcode content, we solved our problem with a Kodi add-on.

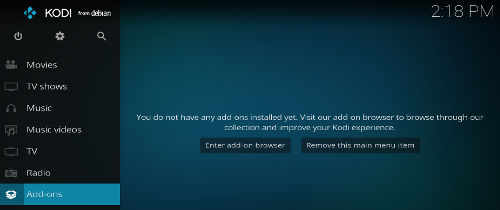

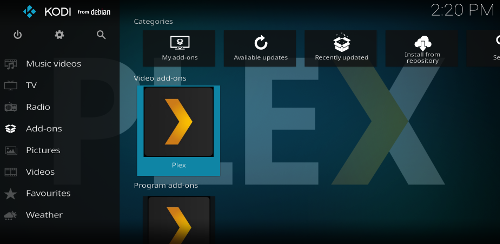

To show how to install an add-on, I’ll use Plex as an example. First, click on Add-ons in the side panel and select Enter add-on browser. Either use the search function or scroll down until you find Plex.

Select the Plex add-on and click the Install button in the lower right-hand corner.

Once the download completes, you can access Plex on the main Kodi screen under Add-ons.

There are several ways to configure an add-on. Some add-ons, such as NHL TV, are configured via a menu accessed by right-clicking the add-on and selecting Configure. Others, such as Plex, display a configuration walk-through when they launch. If an add-on doesn’t seem to be configured when you first launch it, try right-clicking its menu and see if a settings option is available there.

In our house, we have multiple machines that run Kodi. By default, Kodi tracks metadata, such as a video’s watched status and show information, locally. Therefore, content updates on one machine won’t appear on any other machine—unless you configure all your Kodi devices to store metadata inside an SQL database (which is a feature Kodi supports). This technique is not particularly difficult, but it is more advanced. If you’re willing to put in the effort, here’s how to do it.

Before you begin

There are a few things you need to know before configuring shared status for Kodi.

- All content must be on a network share (Samba, NFS, etc.).

- All content must be mounted via the network protocol, even if the disks are local to the machine. That means that no matter where the content is physically located, each client must be configured to use a network fileshare source.

- You need to be running an SQL-style database. Kodi’s official guide walks through MySQL, but I chose MariaDB.

- All clients need to have the database port open (port 3306 in the case of MySQL/MariaDB) or the firewalls disabled.

- All clients must be running the same version of Kodi

If you’re running Ubuntu, you can install MariaDB with the following commands:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install mariadb-server -y

I am running MariaDB on an Arch Linux machine. The Arch Wiki documents the initial setup process well, but I’ll summarize it here.

To install, issue the following command:

sudo pacman -S mariadb

Most distributions of MariaDB will have the same setup commands. I recommend that you understand what the commands do, but you can safely take the defaults if you’re in a home environment.

sudo systemctl start mariadb

sudo mysql_install_db –user=mysql –basedir=/usr –datadir=/var/lib/mysql

sudo mysql_secure_installation

Next, edit the MariaDB config file. This file is different depending on your distribution. On Ubuntu, you want to edit /etc/mysql/mariadb.conf.d/50-server.cnf. On Arch, the file is either /etc/my.cnf or /etc/mysql/my.cnf. Locate the line that says bind-address = 127.0.0.1 and change it to your desired Ethernet port’s IP address or to bind-address = 0.0.0.0 if you want it to listen on all interfaces.

Restart the service so the change will take effect:

sudo systemctl restart mariadb

To enable Kodi to write to the database, one of two things needs to happen: You can create the database yourself, or you can let Kodi do it for you. In this case, since the only database on this system is for Kodi, I’ll create a user with the rights to create any databases that Kodi requires. Do NOT do this if the machine runs more than one database.

mysql -u root -p

CREATE USER ‘kodi’ IDENTIFIED BY ‘kodi’;

GRANT ALL ON *.* TO ‘kodi’;

flush privileges;

\q

This grants the user all rights—essentially enabling it to act as a root user. For my purposes, this is fine.

Next, on each Kodi device where you want to share metadata, create the following file: /home/<USER>/.kodi/userdata/advancedsettings.xml. This file can contain a lot of very advanced, tweakable settings. My devices have these settings:

<advancedsettings>

<videodatabase>

<type>mysql</type>

<host>mysql-arch.example.com</host>

<port>3306</port>

<user>kodi</user>

<pass>kodi</pass>

</videodatabase>

<videolibrary>

<importwatchedstate>true</importwatchedstate>

<importresumepoint>true</importresumepoint>

</videolibrary>

<cache>

<!— The three settings will go in this space, between the two network tags. —>

<buffermode>1</buffermode>

<memorysize>322122547</memorysize>

<readfactor>20</readfactor>

</cache>

</advancedsettings>

The <cache> section—which sets how much of a file Kodi will buffer over the network— is optional in this scenario. See the Kodi wiki for a full breakdown of this file and its options.

Once the configuration is complete, it’s a good idea to close and reopen Kodi to make sure the settings are applied.

The final step is configuring all the Kodi clients to use the same network share for all their content. Only one client needs to scrap/refresh the metadata if everything is created successfully. When data is collected, you should see that Kodi creates a new database on your SQL server:

[kodi@kodi-mysql ~]$ mysql -u root -p

Enter password:

Welcome to the MariaDB monitor. Commands end with ; or \g.

Your MariaDB connection id is 180

Server version: 10.1.37-MariaDB MariaDB Server

Copyright (c) 2000, 2018, Oracle, MariaDB Corporation Ab and others.

Type ‘help;’ or ‘\h’ for help. Type ‘\c’ to clear the current input statement.

MariaDB [(none)]> show databases;

+——————–+

| Database |

+——————–+

| MyVideos107 |

| information_schema |

| mysql |

| performance_schema |

+——————–+

4 rows in set (0.00 sec)

Wrapping up

This article walked through how to get up and running with the basic functionality of Kodi. You should be able to add content and pull down metadata to make browsing your media more convenient.

You also know how to search for, install, and potentially configure add-ons for additional features. Be extra careful when downloading add-ons, as they are provided by the community at large and not the core developers. It’s best to use add-ons only from organizations or companies you trust.

And you know a bit about sharing metadata across multiple devices. You’ve been introduced to advancedsettings.xml; hopefully it has piqued your interest. Kodi has a lot of dials and knobs to turn, and you can squeeze a lot of performance and functionality out of the platform with enough experimentation.

Aaeon’s compact, fanless “Boxer-8110AI” embedded computer runs Ubuntu 16.04 on an Nvidia Jetson TX2 module and offers GbE, HDMI, CAN, serial, and 3x USB ports, plus anti-vibration and -20 to 50°C support.

Aaeon’s compact, fanless “Boxer-8110AI” embedded computer runs Ubuntu 16.04 on an Nvidia Jetson TX2 module and offers GbE, HDMI, CAN, serial, and 3x USB ports, plus anti-vibration and -20 to 50°C support.