You can find grep present deep inside the animal brain of Unix and Unix-like operating systems. It is a basic program used for pattern matching and it was written in the 70s along with the rest of the UNIX tool that we know and love (or hate).

While learning about formal languages and regular expressions is an exciting topic. Learning grep has a lot more to it than regexes. To get started with it and to see the beauty and elegance of grep you need to see some real-world examples, first.

Examples which are handy and make your life a little easier. Here are 30 such grep commonplace use cases and options.

1. ps aux | grep <pattern>

The ps aux list all the processes and their associated pids. But often this list is too long for a human to inspect. Piping the output to a grep command you can list processes running with a very specific application in mind. For example the <pattern> could be sshd or nginx or httpd.

# ps aux | grep sshd

root 400 0.0 0.2 69944 5624 ? Ss 17:47 0:00 /usr/sbin/sshd -D

root 1076 0.2 0.3 95204 6816 ? Ss 18:29 0:00 sshd: root@pts/0

root 1093 0.0 0.0 12784 932 pts/0 S+ 18:29 0:00 grep sshd

2. Grepping your IP addresses

In most operating systems you can list all your network interfaces and the IP that is assigned to that interface by using either the command ifconfig or ip addr. Both these commands will output a lot of additional information. But if you want to print only the IP address (say for shell scripts) then you can use the command below:

$ ip addr | grep inet | awk ‘{ print $2; }’

$ ip addr | grep -w inet | awk ‘{ print $2; }’ #For lines with just inet not inet6 (IPv6)

The ip addr command gets all the details (including the IP addresses), it is then piped to the second command grep inet which outputs only the lines with inet in them. This is then piped into awk print the statement which prints the second word in each line (to put it simply).

P.S: You can also do this without the grep if you know awk well know.

3. Looking at failed SSH attempts

If you have an Internet facing server, with a public IP, it will constantly be bombarded with SSH attempts and if you allow users to have password based SSH access (a policy that I would not recommend) you can see all such failed attempts using the following grep command:

# cat /var/log/auth.log | grep “Fail”

Sample out put

Dec 5 16:20:03 debian sshd[509]:Failed password for root from 192.168.0.100 port 52374 ssh2

Dec 5 16:20:07 debian sshd[509]:Failed password for root from 192.168.0.100 port 52374 ssh2

Dec 5 16:20:11 debian sshd[509]:Failed password for root from 192.168.0.100 port 52374 ssh2

4. Piping Grep to Uniq

Sometimes, grep will output a lot of information. In the above example, a single IP may have been attempting to enter your system. In most cases, there are only a handful of such offending IPs that you need to uniquely identify and blacklist.

# cat /var/log/auth.log | grep “Fail” | uniq -f 3

The uniq command is supposed to print only the unique lines. The uniq -f 3 skips the first three fields (to overlook the timestamps which are never repeated) and then starts looking for unique lines.

5. Grepping for Error Messages

Using Grep for access and error logs is not limited to SSH only. Web servers (like Nginx) log error and access logs quite meticulously. If you set up monitoring scripts that send you alerts when grep “404” returns a new value. That can be quite useful.

# grep -w “404” /var/www/nginx/access.log

192.168.0.100 – – [06/Dec/2018:02:20:29 +0530] “GET /favicon.ico HTTP/1.1” 404 200

“http://192.168.0.102/” “Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)

AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/70.0.3538.110 Safari/537.36”

192.168.0.101 – – [06/Dec/2018:02:45:16 +0530] “GET /favicon.ico HTTP/1.1” 404 143

“http://192.168.0.102/” “Mozilla/5.0 (iPad; CPU OS 12_1 like Mac OS X)

AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/12.0 Mobile/15E148 Safari/604.1”

The regex may not be “404” but some other regex filtering for only Mobile clients or only Apple devices viewing a webpage. This allows you to have a deeper insight at how your app is performing.

6. Package Listing

For Debian based systems, dpkg -l lists all the packages installed on your system. You can pipe that into a grep command to look for packages belonging to a specific application. For example:

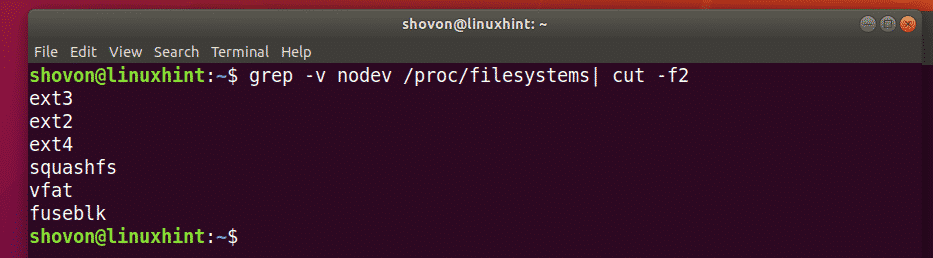

7. grep -v <pattern> fileNames

To list all the lines which don’t contain a given pattern, use the flag -v. It is basically the opposite of a regular grep command.

8. grep -l <pattern>

It lists all the files that contain at least one occurrence of the supplied pattern. This is useful when you are searching for a pattern inside a directory with multiple files. It only prints the file name, and not the specific line with the pattern.

9. Single word option -w

$ grep -w <PATTERN> fileNames

The -w flag tells grep to look for the given pattern as a whole word and not just a substring of a line. For example, earlier we grepped for IP address and the pattern inet printed the lines with both inet and inet6 listing both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses. But if we used -w flag only the lines with inet as a word preceded and followed by white spaces is a valid match.

10. Extended Regular Expression

You will often find that the regular expressions native to Grep are a bit limiting. In most scripts and instructions you will find the use of -E flag and this will allow you to enter pattern in what is called the Extended Mode.

Here’s the grep and grep -E commands to look for words Superman and Spiderman.

$ grep “(Super|Spider)man” text

$ grep -E “(Super|Spider)man” text

As you can see the extended version is much easier to read.

11. Grep for your containers

If you have a large cluster of containers running on your host, you can grep them by image name, status, ports they are exposing and many other attributes. For example,

$ docker ps | grep [imageName]

12. Grep for your pods

While we are on the topic of containers. Kubernetes often tend to launch multiple pods under a given deployment. While each pod has a unique name, in a given namespace, they do start with the deployment name, typically. We can grep of that and list all the pods associated with a given deployment.

$ kubectl get pods | grep <deploymentName>

13. Grep for Big data

Often times the so called “Big Data” analysis involves simple searching, sorting and counting of patterns in a given dataset. Low level UNIX utilities like grep, uniq, wc are especially good at this. This blog post shows a nice example of a task accomplished in mere seconds using grep and other Unix utilities while Hadoop took almost half an hour.

For example, this data set is over 1.7GB in size. It contains information about a multitude of chess matches, including the moves made, who won, etc. We are interested in just results so we run the following command:

$ grep “Result” millionbase-2.22.pgn | sort | uniq -c

221 [Result “*”]

653728 [Result “0-1”]

852305 [Result “1-0”]

690934 [Result “1/2-1/2”]

This took around 15 seconds on a 4 year old 2-cores/4-thread processor. So the next time you are solving a “big data” problem. Think if you can use grep instead.

14. grep –color=auto <PATTERN>

This option lets grep highlight the pattern inside the line where it was found.

15. grep -i <PATTERN>

Grep pattern matching is inherently case-sensitive. But if you don’t care about that then using the -i flag will make grep case insensitive.

16. grep -n

The -n flag will show the line numbers so you don’t have to worry finding the same line later on.

17. git grep

Git, the version control system, itself has a built-in grep command that works pretty much like your regular grep. But it can be used to search for patterns on any committed tree using the native git CLI, instead of tedious pipes. For example, if you are in the master branch of your repo you can grep across the repo using:

(master) $ git grep <pattern>

18. grep -o <PATTERN>

The -o flag is really helpful when you are trying to debug a regex. It will print only the matching part of the line, instead of the entire line. So, in case, you are getting too many unwanted line for a supplied pattern, and you can’t understand why that is happening. You can use the -o flag to print the offending substring and reason about your regex backwards from there.

19. grep -x <PATTERN>

The -x flag would print a line, if and only if, the whole line matches your supplied regex. This is somewhat similar to the -w flag which printed a line if and only of a whole word matched the supplied regex.

20. grep -T <PATTERN>

When dealing with logs and outputs from a shell scripts, you are more than likely to encounter hard tabs to differentiate between different columns of output. The -T flag will neatly align these tabs so the columns are neatly arranged, making the output human readable.

21. grep -q <PATTERN>

This suppresses the output and quietly runs the grep command. Very useful when replacing text, or running grep in a daemon script.

22. grep -P <PATTERN>

People who are used to perl regular expression syntax can use the -P flag to use exactly that. You don’t have to learn basic regular expression, which grep uses by default.

23. grep -D [ACTION]

In Unix, almost everything can be treated as a file. Consequently, any device, a socket, or a FIFO stream of data can be fed to grep. You can use the -D flag follow by an ACTION (the default action is READ). A few other options are SKIP to silently skip specific devices and RECURSE to recursively go through directories and symlinks.

24. Repetition

If are looking for given pattern which is a repetition of a known simpler pattern, then use curly braces to indicate the number of repetition

This prints lines containing strings 10 or more digits long.

25. Repetition shorthands

Some special characters are reserved for a specific kind of pattern repetition. You can use these instead of curly braces, if they fit your need.

? : The pattern preceding question mark should match zero or one time.

* : The pattern preceding star should match zero or more times.

+ : The pattern preceding plus should match one or more times.

25. Byte Offsets

If you want to know see the byte offset of the lines where the matching expression is found, you can use the -b flag to print the offsets too. To print the offset of just the matching part of a line, you can use the -b flag with -o flag.

$ grep -b -o <PATTERN> [fileName]

Offset simply mean, after how many byte from the beginning of the file does the matching string start.

26. egrep, fgrep and rgerp

You will often see the invocation of egrep, to use the extended regular expression syntax we discussed earlier. However, this is a deprecated syntax and it is recommended that you avoid using this. Use grep -E instead. Similarly, use grep -F, instead of fgrep and grep -r instead of rgrep.

27. grep -z

Sometimes the input to grep is not lines ending with a newline character. For example, if you are processing a list of file names, they might come through from different sources. The -z flag tells grep to treat the NULL character as the line ending. This allows you to treat the incoming stream as any regular text file.

28. grep -a <PATTERN> [fileName]

The -a flag tells grep to treat the supplied file as if it were regular text. The file could be a binary, but grep will treat the contents inside, as though they are text.

29. grep -U <PATTERN> [fileName]

The -U flag tells grep to treat the supplied files as though they are binary files and not text. By default grep guesses the file type by looking at the first few bytes. Using this flag overrules that guess work.

30. grep -m NUM

With large files, grepping for an expression can take forever. However, if you want to check for only first NUM numbers of matches you can use the -m flag to accomplish this. It is quicker and the output is often manageable as well.

Conclusion

A lot of everyday job of a sysadmin involves sifting through large swaths of text. These may be security logs, logs from your web or mail server, user activity or even large text of man pages. Grep gives you that extra bit of flexibility when dealing with these use cases.

Hopefully, the above few examples and use cases have helped you in better understanding this living fossil of a software.

Source

How to install Node.js with npm on CentOS 7

How to install Node.js with npm on CentOS 7 How to install Node.js and npm using nvm on CentOS 7

How to install Node.js and npm using nvm on CentOS 7