This tutorial shows you how to update Ubuntu for both server and desktop versions. It also explains the difference between update and upgrade along with a few other things you should know about updates in Ubuntu Linux.

If you are a new user and have been using Ubuntu for a few days or weeks, you might be wondering how to update your Ubuntu system for security patches, bug fixes and application upgrades.

Updating Ubuntu is absolutely simple. I am not exaggerating. It’s as simple as running two commands. Let me give you more details on it.

Please note that the tutorial is valid for Ubuntu 18.04, 16.04 or any other version. The command line way is also valid for Ubuntu-based distributions like Linux Mint, Linux Lite, elementary OS etc.

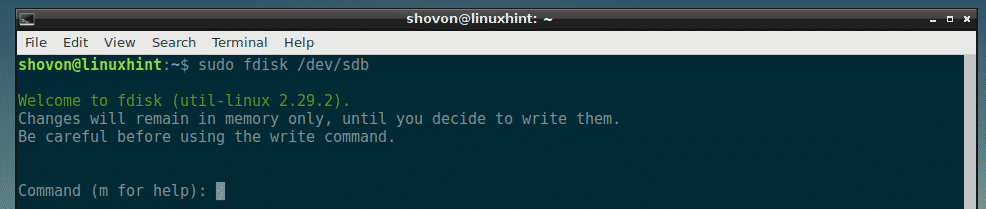

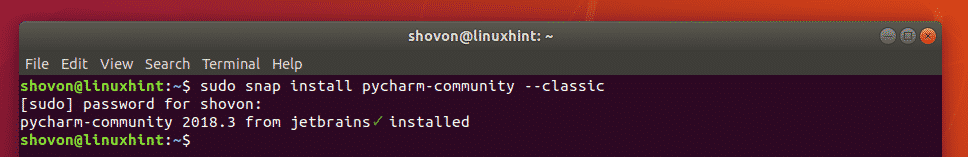

Update Ubuntu via Command Line

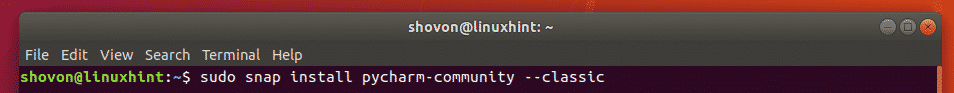

On the desktop, open the terminal. You can find it in the menu or use the Ctrl+Alt+T keyboard shortcut. If you are logged on to an Ubuntu server, you already have access to a terminal.

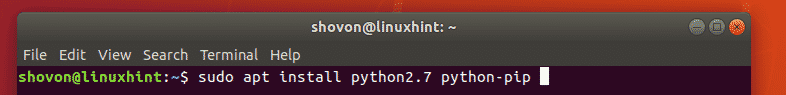

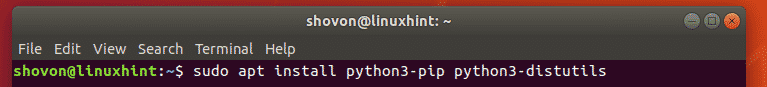

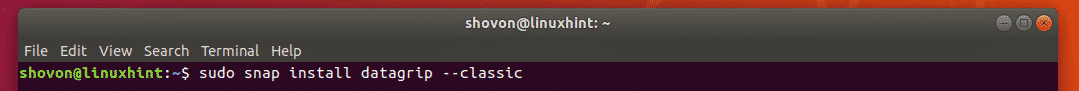

In the terminal, you just have to use the following command:

sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade -y

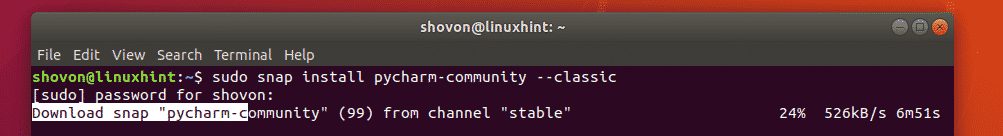

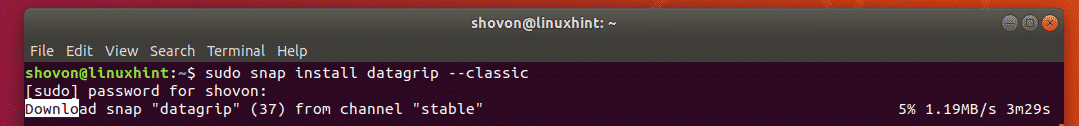

It will ask for password and you can use your account’s password. You won’t see the anything on the screen while typing so keep on typing your password and hit enter.

Now let me explain the above command.

Actually, it’s not a single command. It’s a combination of two commands. The && is a way to combine two commands in a way that the second command runs only when the previous command ran successfully.

The ‘-y’ in the end automatically enters yes when the command ‘apt upgrade’ ask for your confirmation before installing the updates.

Note that you can also use the two commands separately, one by one:

sudo apt update

sudo apt upgrade

It will take a little longer because you have to wait for one command to finish and then enter the second command.

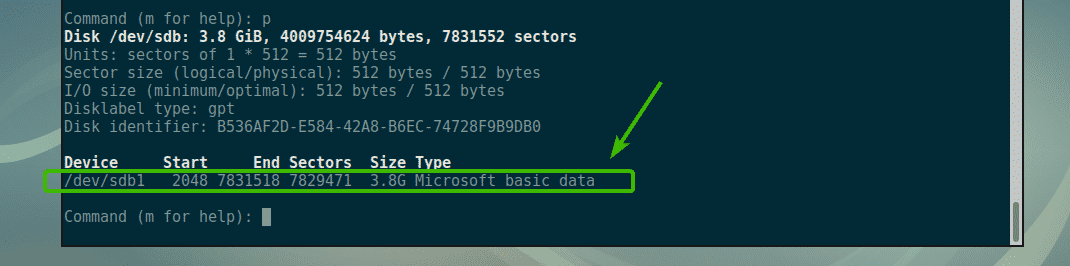

Explanation: sudo apt update

This command updates the local database of available packages. If you won’t run this command, the local database won’t be updated and your system will not know if there are any new versions available.

This is why when you run the sudo apt update, you’ll see lots of URLs in the output. The command fetches the package information from the respective repositories (the URLs you see in the output).

At the end of the command, it tells you how many packages can be upgraded. You can see these packages by running the following command:

apt list –upgradable

Additional Reading: Read this article to learn what is Ign, Hit and Get in the apt update command output.

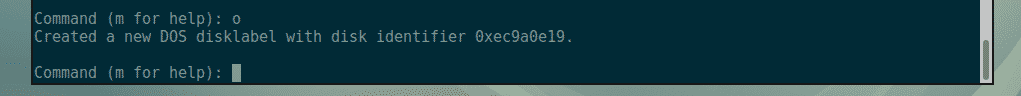

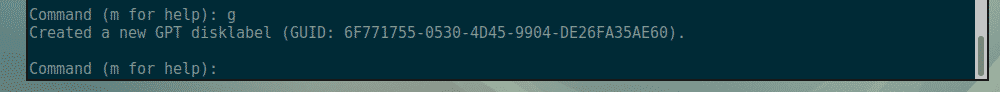

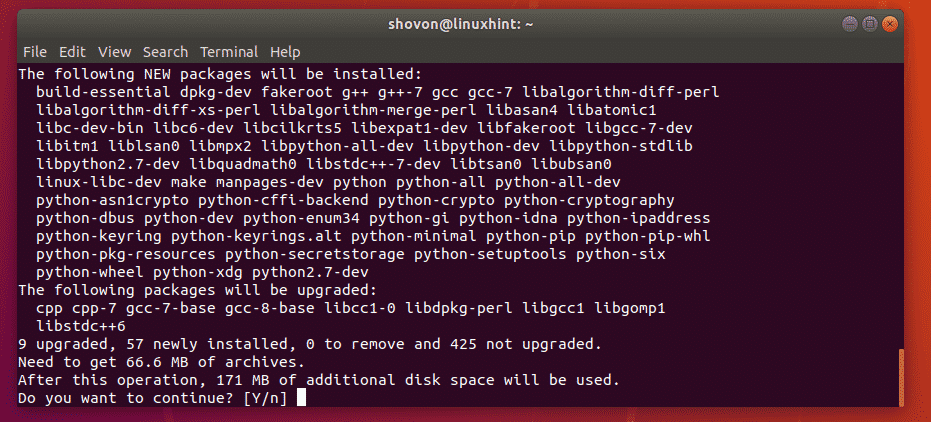

Explanation: sudo apt upgrade

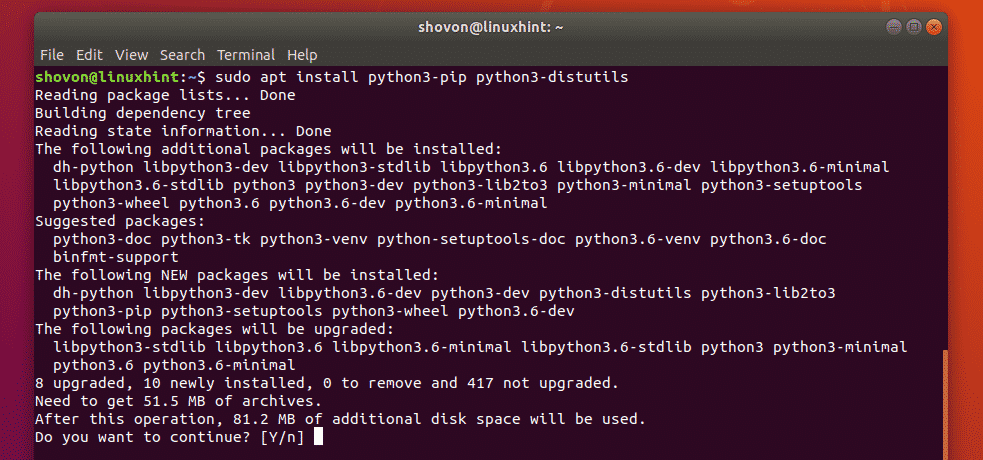

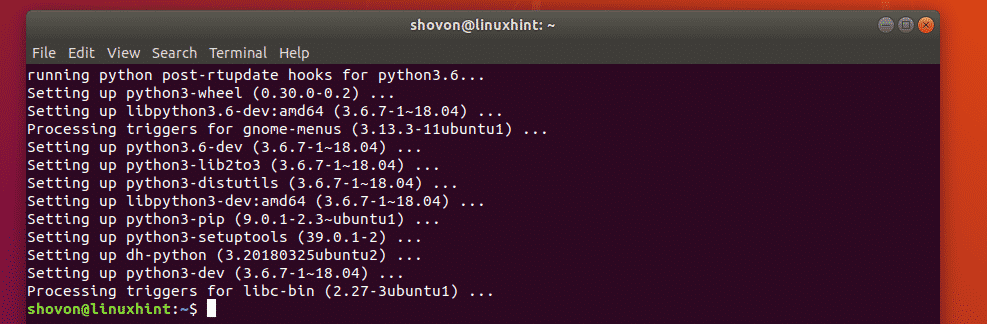

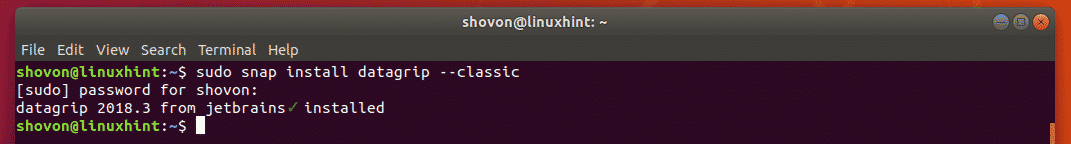

This command matches the versions of installed packages with the local database. It collects all of them and then it will list all of the packages that have a newer version available. At this point, it will ask if you want to upgrade (the installed packages to the newer version).

You can type ‘yes’, ‘y’ or just press enter to confirm the installation of updates.

So the bottom line is that the sudo apt update checks for the availability of new versions while as the sudo apt upgrade actually performs the update.

The term update might be confusing as you might expect the apt update command to update the system by installing the updates but that doesn’t happen.

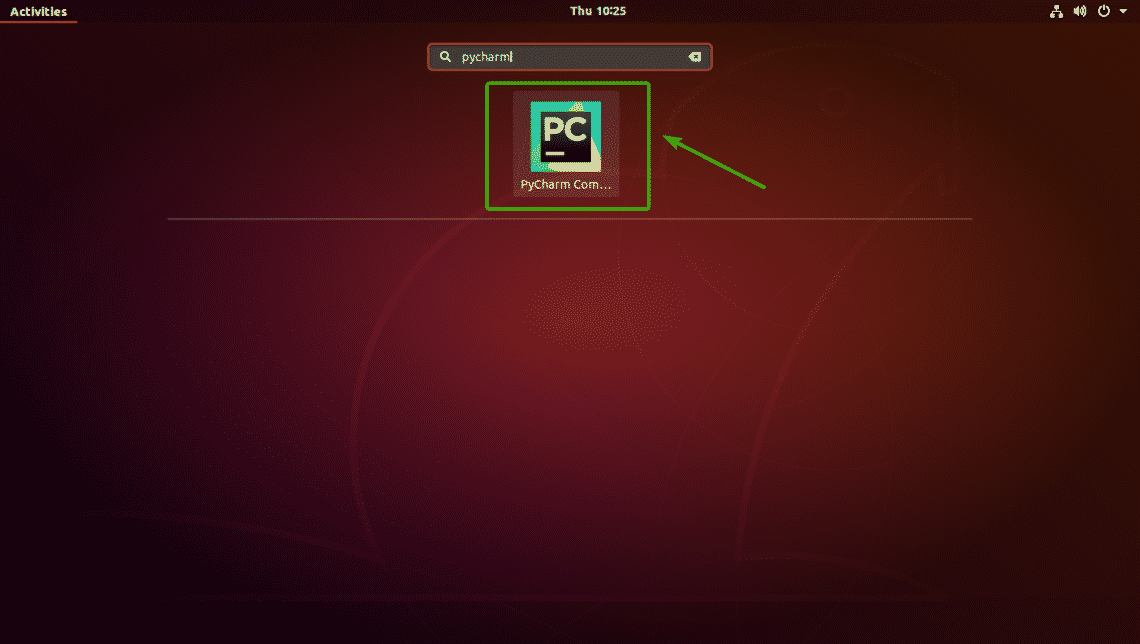

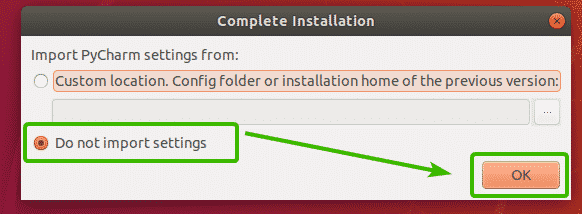

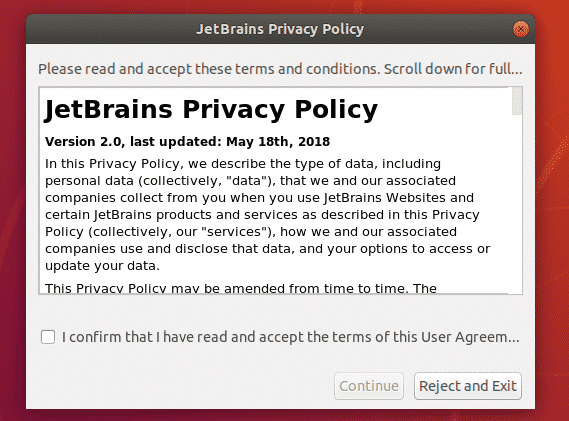

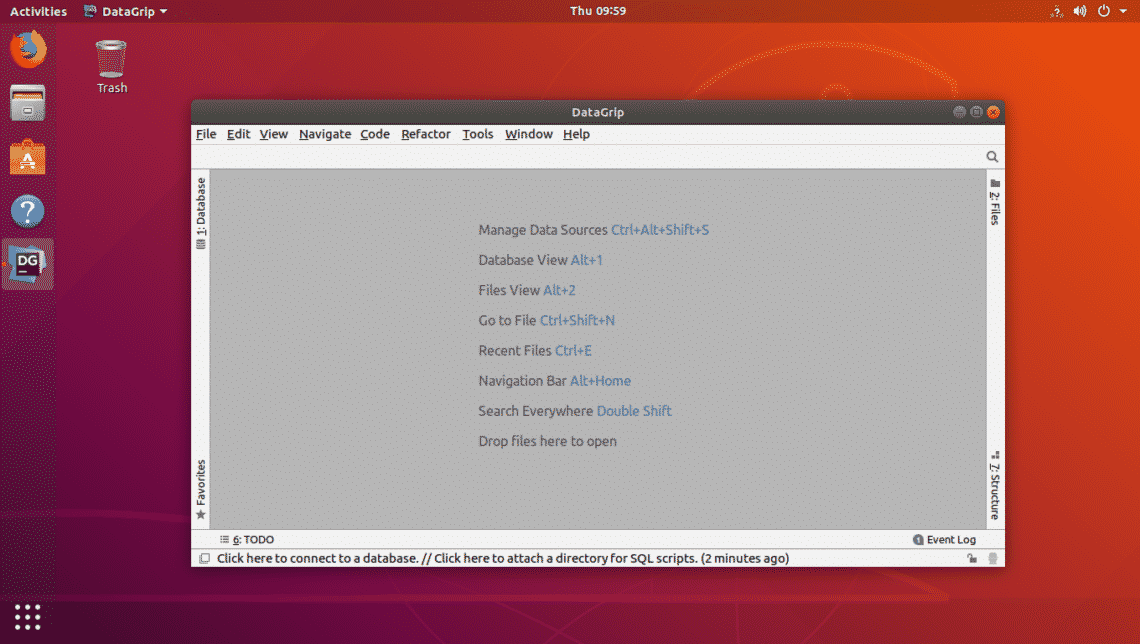

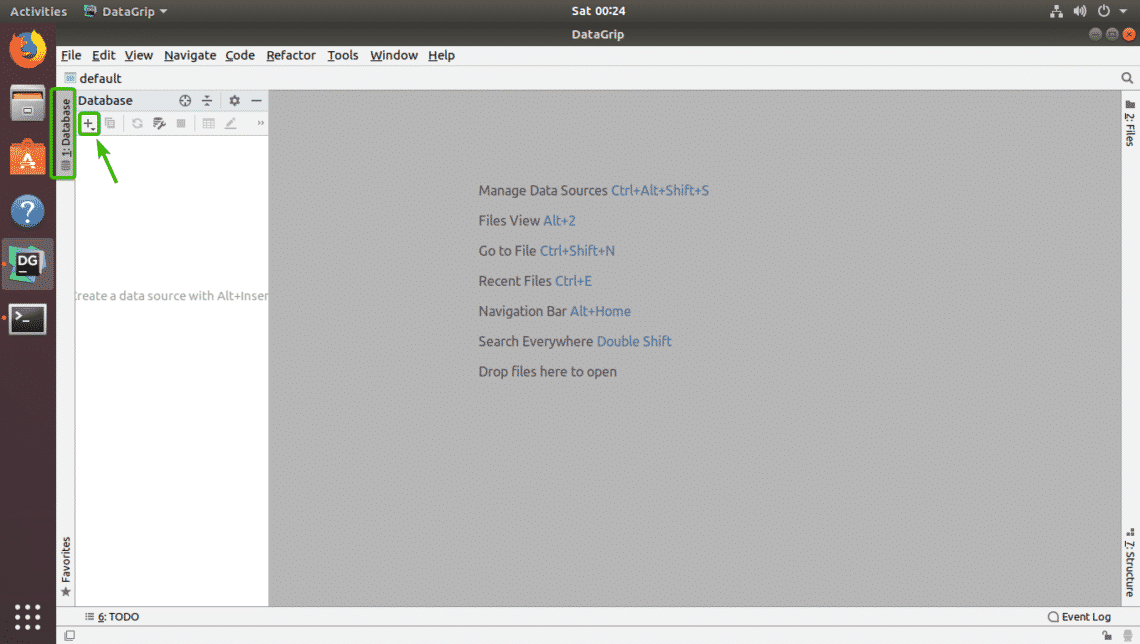

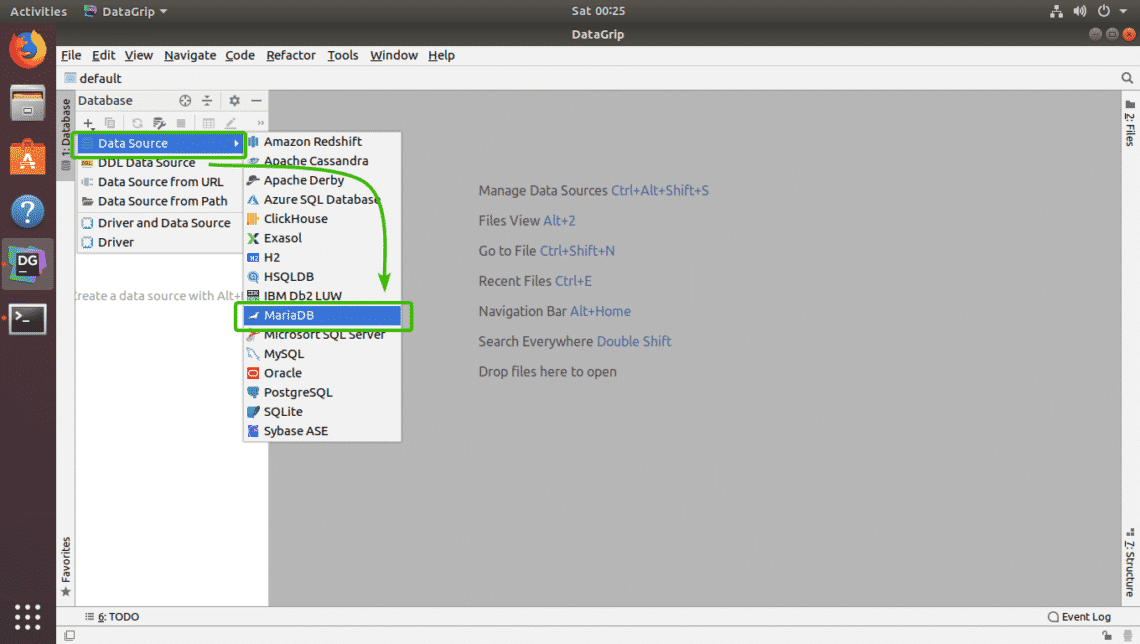

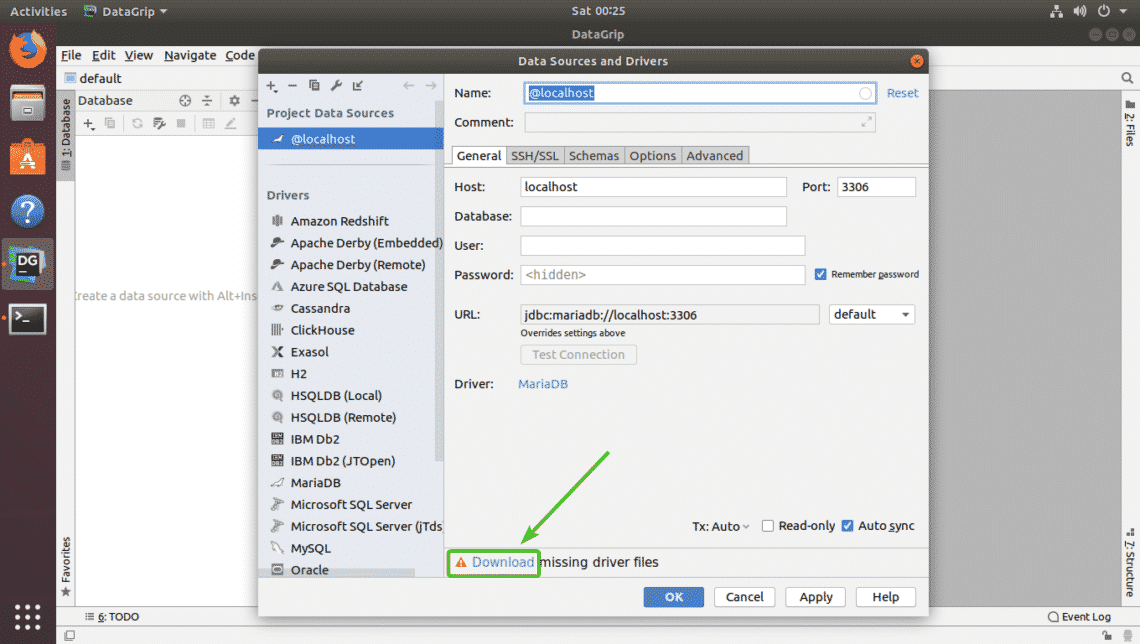

Update Ubuntu via GUI [For Desktop Users]

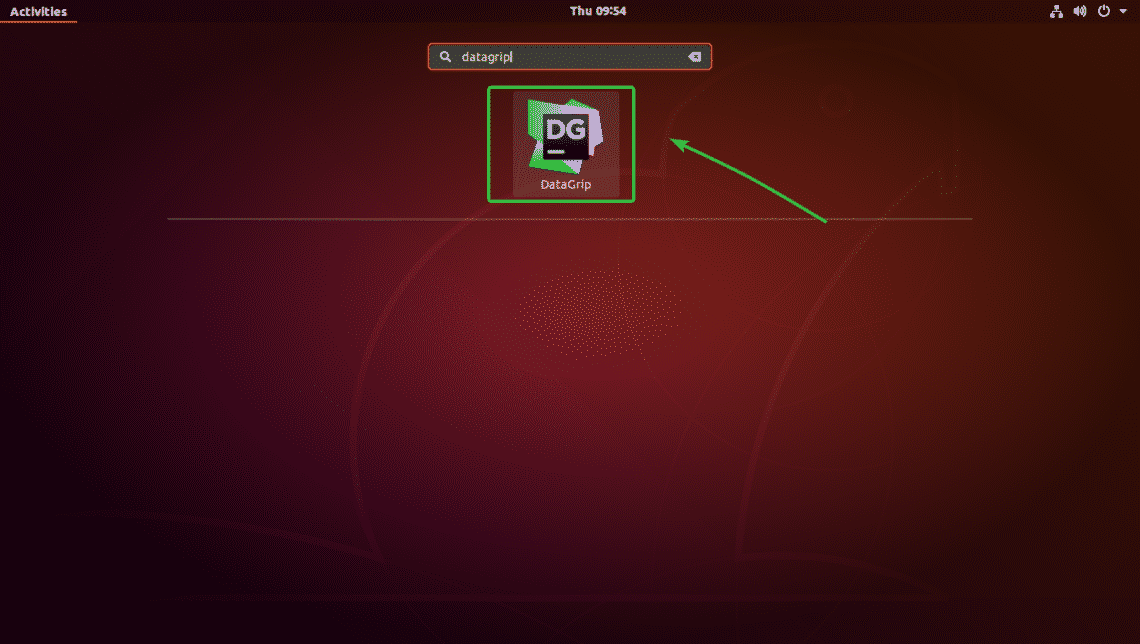

If you are using Ubuntu as a desktop, you don’t have to go to terminal just for updating the system. You can still use the command line but it’s optional for you.

In the menu, look for ‘Software Updater’ and run it.

It will check if there are updates available for your system.

If there are updates available, it will give provide you with options to install the updates.

Click on Install Now, it may ask for your password.

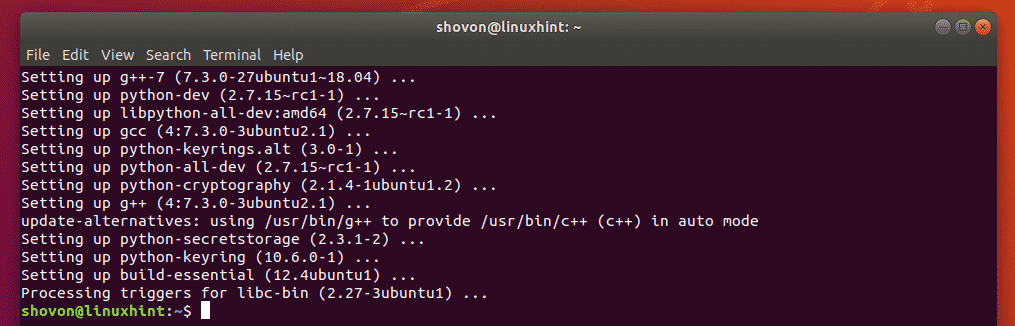

Once you enter your password, it will start installing the updates.

In some cases, you may need to reboot the system for the installed updates to work properly. You’ll be notified at the end of the update if you need to restart the system.

You can choose to restart later if you don’t want to reboot your system straightaway.

Tip: If the software updater returns an error, you should use the command ‘sudo apt update’ in the terminal. The last few lines of the output will contain the actual error message. You can search on the internet for that error and fix the problem.

Few things to keep in mind abou updating Ubuntu

You just learned how to update your Ubuntu system. If you are interested, you should also know these few things around Ubuntu updates.

Clean up after an update

Your system will have some unnecessary packages that won’t be required after the updates. You can remove such packages and free up some space using this command:

sudo apt autoremove

Live patching kernel in Ubuntu Server to avoid rebooting

In case of a Linux kernel updates, you’ll have to restart the system after the update. This is an issue when you don’t want downtime for your server.

Live patching feature allows the patching of Linux kernel while the kernel is still running. In other words, you don’t have to reboot your system.

If you manage servers, you may want to enable live patching in Ubuntu.

Version upgrades are different

The updates discussed here is to keep your Ubuntu install fresh and updated. It doesn’t cover the version upgrades (for example upgrading Ubuntu 16.04 to 18.04).

Ubuntu version upgrades are entirely a different thing. It updates the entire operating system core. You need to make proper backups before starting this lengthy process.